Welcome to the final installment of this four-part Weird Luck interview series? In parts one, two, and three, press partners Andrew M. Reichart and Nick Walker talked about the origins of Weird Luck, their unique approach to worldbuilding, neurodivergence in the WL universe, and the expandable possibilities of the WL multiverse. In this week’s installment, you’ll read the backstory of the WL comic, plus Andrew and Nick reveal the future of WL and give us details about the Argawarga relaunch.

– N.I. Nicholson

Ian: Now I’m thinking about the recent discussion about the webcomic in this whole thread and wondering: at what point did you all decide to include and launch a webcomic in the Weird Luck, and what spurred the idea?

Nick: I bear the blame for the idea of doing a webcomic.

Comics were a central obsession for me throughout my childhood and teen years. I mean, I wasn’t just another kid who loved comic books; I was drawing comics before I could write, and while I was still in grade school I acquired an encyclopedic knowledge of the history of comics — not just comic books but newspaper comic strips all the way back to the days of The Yellow Kid and Mutt & Jeff.

In fact, Agent Sojac’s name comes from the nonsense phrase “Notary Sojac,” which regularly appeared on signs and such in the backgrounds of the old absurdist newspaper comic strip Smokey Stover. That’s what kind of comics geek I am.

But once I was out of high school, the struggle to survive as an autistic person with no financial resources or familial support derailed my plans to pursue a career in comics. Too busy just trying not to be homeless, and by the time I had enough stability in my life to make substantial creative projects viable I’d gotten sidetracked into other things. I got into writing eventually, but not back into creating comics.

Meanwhile, from 1996 to 2015, I was a core member of a group called Paratheatrical Research. The work of Paratheatrical Research involved using a combination of intensive physical movement work and trance states to access and forces in the personal and collective unconscious. Essentially doing deep Jungian work via the methods of experimental physical theatre.

Andrew got involved in Paratheatrical Research as well. In 2013, we were involved in some Paratheatrical Research work that focused on exploring the archetypal forces known as the Muses. When I started connecting with the Muses, they made it quite clear to me that it was time to get back to the creative dreams of my youth — writing fun weird speculative fiction, and making comics.

By that time, I’d become a fan of several webcomics, and really liked the medium — especially its DIY accessibility and the way it fostered regular reader/creator engagement.

So one day in the Spring of 2013, Andrew and I were walking to a Paratheatrical Research session together, and I proposed out of the blue that we collaborate on a webcomic. Of course, the idea that it would be part of the Weird Luck saga went without saying, because it was me and Andrew.

It took a while to get rolling. We realized that the two of us didn’t have time to both write and draw it, certainly not draw it at the level of skill we were envisioning, so we had to find an artist who was into the idea. Eventually, Andrew got the extraordinarily talented Mike Bennewitz on board — Mike was already the cover artist for Andrew’s Weird Luck novels.

Then we spent a while experimenting with what proved to be a false start. See, the main setting of the Weird Luck webcomic is the city-state of Tal Sharnis, which was created when an interdimensional disaster caused two cities in different universes to merge with one another into one reality-warped hybrid city (the disaster also tore both cities out of their native universes and transported them to the desolate chaotic wasteland of the Plateau of Leng). One of the two cities that got fused together in this disaster was also called Tal Sharnis, and before the disaster (which everyone now calls the Great Merger) it was located on Amarantis, a world that plays an important role in the Weird Luck saga. The other city was a version of late-20th-Century San Francisco (well, really the greater San Francisco Bay Area, including Oakland, Berkeley, the Marin headlands, and the Bay itself).

Well, the original plan was for the webcomic to take place in this version of San Francisco in the time shortly BEFORE the Great Merger. When it was still San Francisco, and still located on a version of modern-day Earth, but reality is starting to come apart at the seams a bit as the moment of the Great Merger slowly approaches.

We spent a bunch of time working on that story before we realized it wasn’t catching fire for us as a team. Mike wanted to draw exotic alien locations, and wanted some of the characters he drew to be nonhuman and/or too wildly exotic to blend in on 20th Century Earth. Andrew and I wanted a story that would connect more closely with Andrew’s novels, a story where we could bring in space pirates and that sort of thing.

So we went back to the drawing board, and in the end the result is the Weird Luck webcomic we’ve got today, which we’re having a great time with and which is proving to fit perfectly with the sort of Weird Luck prose stories we’re feeling inspired to write these days.

That prequel story in the pre-Merger Bay Area, though… that story is going to be told someday. I might do it as a second webcomic with a different artist who likes drawing modern-era city life, or maybe as a solo novel, somewhere quite a ways down the road.

Man, nothing about Weird Luck has a short answer…

Ian: Wow. That is pretty fascinating. That managed to answer two of the next follow-up questions I had planned. But your mention of the novels brings me to this question: Tell us a little about the origins of Argawarga Press.

Andrew: In the late 90s, I figured I should grab some sorta unique domain name before they were all snatched up by ‘domain name trolls.’ I picked ‘argawarga.’ In Riddley Walker by Russell Hoban, arga warga is onomatopoeia for the sound of being eaten alive by wild dogs. I read that book once and it changed my life. The word appeals to me because I’m a werewolf, I guess.

Now we’re turning a big corner, becoming an imprint of Autonomous Press, relaunching with the publication of our first non-Andrew book, Dora Raymaker’s Hoshi and the Red City Circuit.

– Andrew M. Reichart

Argawarga dot com was a Web 1.0 static HTML site that I wrote by hand. Basically a porto-blog, consisting of my writing and art. I wrote a couple of books, got an agent. He wasn’t able to get any traction with the books, bless him, partly because he wasn’t very experienced, and partly because they didn’t fit any mainstream market at the time. They’d be fine in the late 60s or early 70s, maybe, but they were far too skinny and genre-bendy for the 00s.

Not long after, though, self-publishing took a turn thanks to ebooks and print-on-demand. We now lived in a world where you didn’t run the risk of printing thousands of copies that sit in storage till you figure out how to move them. I’d had an interest in self-publishing forever, since the punk zines of the 80s, really. But two mentors inspired me to finally undertake it now: Micaela Petersen of Sto*Nerd Press and The Blunt Letters, and Clint Marsh of Wonderella Printed and the journal Fiddler’s Green. Their projects were very different from what I was proposing to do, but their gumption and vision made it seem perfectly reasonable to just, like, offer bound printed matter to the public.

So, I published my first two books under Argawarga Press. And then my third, and my fourth. And now we’re turning a big corner, becoming an imprint of Autonomous Press, relaunching with the publication of our first non-Andrew book, Dora Raymaker’s Hoshi and the Red City Circuit.

Ian: Without giving away too many spoilers, what do the both of you envision for the future of Weird Luck as well as the newly launched Argawarga imprint?

Nick: We’re going to keep on writing and publishing Weird Luck stories for a long time to come. We have a lot of story to tell, and we keep on generating more. As I noted earlier, what’s been published so far is the very small tip of a very big iceberg.

We’re in the early stages of co-writing a series of Weird Luck novels, which will initially be published in weekly installments on the Weird Luck website and will eventually become available in paperback from the Argawarga Press imprint. Insurgent Otherworld is the first of these collaborative novels; it will be followed by Gods of the Endless Plateau, and then others in the years to come.

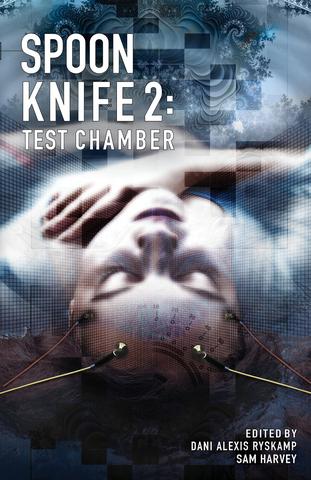

In late spring of this year, Autonomous Press publishes Spoon Knife 3: Incursions, the third volume of the annual Spoon Knife literary anthology. Andrew and I were the editors for this volume, and, like the previous volume, this one features two new Weird Luck short stories — one from each of us. We aim to continue releasing new Weird Luck short stories in every future volume of Spoon Knife.

The webcomic has been on hiatus for a bit, but new webcomic pages are in the works. We’re just getting into the part of the webcomic that introduces Smiley, one of the central characters in the Weird Luck saga. Readers already got to meet a much younger Smiley in my novelette “Bianca and the Wu-Hernandez,” which appeared in volume two of Spoon Knife. The middle-aged Smiley of the webcomic is even more troublesome. Middle-aged Smiley is also the protagonist of my upcoming story in Spoon Knife 3: Incursions. Smiley has a gift for making any situation a whole lot more complicated and chaotic than it needs to be, so we’re looking forward to springing him on Agent Sojac and the rest of the gang in Tal Sharnis.

Andrew: As for Argawarga Press, we’ve got a big couple of years ahead, with five Weird Luck titles forthcoming — re-releases of my four books in new paperback and ebook editions, plus Insurgent Otherworld. Then when we finish Gods of the Endless Plateau, Argawarga will publish it as well, probably in 2020.

We’ve also got books coming out that are (as far as we know) outside the Weird Luck Saga: the aforementioned Hoshi and the Red City Circuit by Dora Raymaker, and a sort of tangential prequel, Resonance, which may come out as soon as next year. And she’s got a direct sequel brewing, which will make Hoshi fans glad.

Finally, for folks who like rare collectible stuff, I guess I could mention that every year I make a limited edition zine/chapbook, Weird Luck Tales, that includes a couple of Weird Luck stories. There are still a few copies left of last year’s No. 5, featuring my story “Monsters” from Spoon Knife 2: Test Chamber, plus “Things that Crawled from the Shadows,” which appeared on weirdluck.org. I made two limited editions of 99 copies each, one for the Outer Dark Symposium on the Greater Weird, and one for NecronomiCon in Providence. I’m in the process of making the exclusive edition for participants in this year’s Outer Dark Symposium, and I’ll have a second limited edition for sale later in the spring. Weird Luck Tales No. 6 includes my story from Spoon Knife 3: Incursions, “Space Pirate Stowaway,” and the backup story “The Art Collector’s Dream Diary,” published on weirdluck.org this spring.

And I’ve got other Weird Luck stories in the works as well, which I’m submitting to various oddball genre markets. There’s lots of Weird Luck stuff yet to come.

Thanks for reading our Weird Luck interview series! We hope you’ve enjoyed this revealing look at the WL multiverse, the rich backstories behind it and its creators, and the exciting future that lays ahead. To make sure you don’t miss a post, like AutPress on Facebook and follow us on Twitter. While you’re at it, don’t forget to follow the Weird Luck Facebook page for even more WL updates!